|

Covering the walls in front of them is the most fantastic find of paleolithic

art yet found, so old as to boggle the mind.

Whole picture galleries cover the walls for hundreds of meters, all painted with

uncanny realism. Hundreds of horses, stags and ibex. Buffalo, bears, and

reindeer, their mineral colours of red ochre, yellow ochre and black all

masterfully applied.

And even more fantastic animals, so long extinct as to be incomprehensible that

their painter could actually step outside and literally watch them. Alive.

Walking by. Or stalking their prey.

Lions. A red panther. Herds of rhinoceros. And great, towering woolly mammoths.

Painted as they were seen, 30 millennia ago.

All autographed by the creator's own handprints, on the wall of the Chauvet Cave

where he had pressed them against the rock, during the last Ice Age. 31,000

years before.

Invented out of necessity to help satisfy the need for human expression, and

predating even the written word as a means to record What Was Seen, watercolour

was the natural medium of choice for early artists.

The warm earth colours were easily found. Grinding them into a pigment ready for

mixing was a simple enough chore. And so was the actual application, with lots

of drying time with water as the base.

And of messy cleanups - guaranteed centuries later by the introduction of oils -

the early artists were blissfully ignorant.

Brazil: Oldest Rock

Art in New World

Numerous examples of paleolithic art still dot the world, from the mute

testaments of the Bushman, painted on outcrops of rock in the Kalahari Desert,

to ancient hunting scenes in the limestone caves of northeastern Brazil, to

aboriginal rock paintings at Obiri and Unbalanya hill in the outback of

Australia.

The previous record holder for Oldest Paintings are at Altamira Cave in northern

Spain, first seen in 1875 by the little daughter of Marcelo de Sautuola, a

nobleman from nearby Santandar, who visited the cave with her father after it

had been found by a local hunter.

Looking up at the roof of the cave, little Maria called out in wonder at the

whole herd of prehistoric animals populating the ceiling. The 15 bison, 2 wild

boars, and numerous horses are still there today, all executed vigorously by

their unnamed artists, their outlines still sharp and realistic, despite having

been painted 190 centuries ago.

Only slightly younger is another zoo of painted animals. Just a stone's throw

from the Chauvet cave, the Lascaux version is yet another cave, discovered by

two young French boys in 1940. One and a half thousand animals, including

life-sized bulls, ochre cows and grey horses still cavort impishly, even after

13,000 years of unattended confinement.

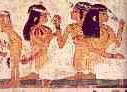

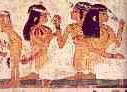

EGYPTIAN SPLENDOR

Fast-forward nine and a half thousand years. The world has left the Stone Age

well behind, having emersed itself in the Bronze Age long enough to realize that

tools and weapons of iron were now on the cutting edge of technology.

Enter the Iron Age. Anything seems possible.

In Egypt, the 18th dynasty rules, and on the banks of the Nile, agriculture

flourishes. Shipping and travel to distant lands becomes second nature.

Sculpture grows to colossal dimensions. And at Giza, in a flurry of

state-of-the-art technology, architecture reaches new heights in the form of the

pyramids.

Watercolourists, too, have improvised a new, high-tech method. Watercolour has

advanced to the fresco stage: that of laying the colour on a wet plaster surface

before it has dried. Royal painters and scribes preserve scenes of everyday life

in the wall murals of their pharaohs' tombs, at least partially achieving their

masters ultimate aim of immortality.

From the beginning, dating back to 3000 BC, the Egyptians were ones to employ

full, polychromatic painting. No more two-colour artwork with black outlines.

Now living colour was the expected norm. And although the Egyptians painted

everything, from statues, to buildings, to walls, it was at frescos they

excelled.

Fresco (Italian for "fresh") had the advantage of providing larger

uninterrupted painting surfaces, both wonderfully clean and flat, free of the

hollows and blemishes inherent in any natural rock face. Fresco too, solved the

annoying problem of the soft, crumbling rock on the walls of the tombs, many of

which were carved into the living rock of the Theban mountains.

To paint in fresco required two teams of craftsmen. The plasterer, who put up

the 'canvas', and the artist, who worked his watercolour magic upon subtle

backgrounds of light blue, grey, or cream, before the plaster dried. Both

craftsmen of such distinction in Egyptian society as to be held on a par with

the status of doctors and hairdressers.

Watercolour pigments now covered a veritable rainbow from red ochres to green

frit to the royal blues of lapus lazuli. Ground as before, and mixed with water

and a small amount of binding agent - to provide uniform adhesion - the fresco

unfolded, from the bristles of a whole family of twig and papyrus reed brushes.

With an eye for detail that even reproduced the subtle variegation of granite or

the growth rings and grain in wood, the pharaohs' biographers left for posterity

a complete panorama of everyday life, from royalty to common fishing scenes, in

the lush, vibrant colours we see today. Painted on the walls of their burial

chambers and entombed for 35 centuries.

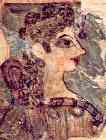

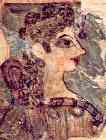

Vibrancy

in Motion: Bull and Acrobats, Knossos Archeological Museum, Heraclion, Crete Vibrancy

in Motion: Bull and Acrobats, Knossos Archeological Museum, Heraclion, Crete

CARRYING THE FRESCO FLAME

Even with the decline and eventual extinguishing of the Egyptian empire, the art

of watercolour fresco enjoyed remarkable longevity, passing from civilization to

civilization down the centuries.

Farther north, the Minoans were also using fresco in 1500 BC for paintings in

the palace of Knossos on present day Crete. Some evidence even suggests an

earlier use, some 500 years before the more stilted forms of Egyptian painting.

The Minoan style is bright and cheerful, almost impressionistic in execution,

with its animated figures exuding a vibrancy and sparkle unseen before. Painted

in what one could only call a tongue-in-cheek manner, they remain today, as full

of the spirited fun and humour as they were painted with, centuries ago.

A thousand years later, in 500 BC, the Etruscans were still utilizing the

remarkably durable fresco technique in the hills of central Italy, filling their

tombs with artwork characterizing the joie de vivre of their life. Dancing,

hunting, sports, plants, birds and foliage, all painted. in fresco on the walls

and ceiling, and in watercolour on the terracotta urns and vessels found within.

The Romans followed suit, when their turn came. The best examples survived

almost intact, entombed in the time capsules of Pompeii and Herculaneum beneath

the ashes of Vesuvius, in 79 AD.

Mars and Venus. Cupid and Vesta. All manner of gods and goddesses grace the

walls of their villas and homes. And quite ordinary mortals too. Most often

portraying the very inhabitants who lived there. And whose tranquil eyes peer

out at us still, with such quiet, steady gaze as to make us wonder what is on

their minds...

THE NEWEST INVENTION: TRANSPARENT COLOURS

Rome has fallen and the Dark Ages descend over Europe like some great funeral

shroud in the wake of its death. In the darkness, the creative arts suddenly

wither and die, like some splendid flower deprived of warmth and light.

It is 300 AD and European painting and watercolour will lie dormant for the next

three centuries.

But not in the East. Art thrives. In China the Han Dynasty has just ended, under

which, for 400 years, a great revival in learning has flourished. Watercolour

has come into its own, having first appeared around 200 BC.

In the hands of Chinese artists watercolour has entered a pivotal point in its

history. The introduction of the clear, transparent watercolour we know today

achieves a delicacy never before seen. Especially in combination with the newest

painting surface, invented in 105 AD. Paper.

First on paper made from wood bark, then on silk, and finally on tougher rice

paper, the haunting beauty of Chinese watercolours is established by such

masters as Ku K'ai-chih (4th century). Using brushes made from pig bristles and

sable, for finer work, he pioneers techniques and landscapes modified by future

generations of artists in China and elsewhere.

In Persia and India the new transparent medium is in use in the 8th century. But

in Japan it arrives slightly earlier, sometime after 500 AD. As in China, it

flourishes.

Japanese art, like its predecessor in China, is marked by sensitive

interpretation, delicate colour and simple design, devoid of confusing

complexities. Fans, panels, screen paintings and, after 700, horizontal scroll

paintings as long as 30 feet document early deities, as well as everyday themes.

During the Fujiwara Period, beginning in 782 and continuing for the next three

centuries, a time of extended peace descends gently over the Japanese

countryside. In the presence of such a climate, free from wars and foreign

intervention, a distinctly Japanese style of watercolours takes root and flowers

prolifically.

Trees, animal life, flowers and romantic landscapes flow forth from the brushes

of artists the like of Kanaoka, by tradition one of the Japan's greatest

painters.

And in some of the earliest examples of actual book production, graceful

watercolours are used for illustrating the retelling of ancient legends. Painted

end-to-end on long scroll paintings accompanying the text, these early works

represent some of the world's earliest illustrated manuscripts.

While watercolour has advanced to transparent-colour-on-paper innovations in the

far east, the tried and true method of fresco art has been in constant use for

two and a half thousand years. Surfacing on its own in far-flung corners of the

world, it thrives independently, in vastly different civilizations.

As early as the fifth century painting of frescos moves east, far from the arid

climates of its birthplace surrounding the Mediterranean Sea. Making inroads on

the Asian subcontinent, it appears in India at the Ajanta caves near Hyderabad,

and in Ceylon on Sigiriya Rock, the already 400 year old palace of King Kasyapa.

Incredibly lifelike murals in fresco in both locations include deities, nymphs

and life-sized dancers, which still cover large galleries with their warm,

bright colours.

Three centuries pass, and half a world away, on an entirely new continent, the

watercolor of fresco surfaces yet again, some 500 years before the arrival of

Old World influence. In what we know today as Central America, watercolor is

rendered on the same wet plaster technique as in ancient Egypt, in the city of

Teotihuacan.

Founded in 300 BC, just northeast of present-day Mexico City, this bustling

metropolis has already thrived for 1200 years as the largest pre-Columbian city

in the Americas. With a population of a quarter million and an area larger than

ancient Rome, it sports highly intricate murals, portraying stylistic gods,

goddesses, and mortal humans.

Elsewhere, far from Mayan territory, but still in the Mexican highlands lies

Cacaxtla, another site adorned in fresco and discovered in 1975. Realistic

warriors and vicious battle scenes come to life in living colour, all edged with

decorative motifs, curiously marine in nature. Sea urchins, crabs and sea

turtles, all painted high and dry, far from any ocean's shores.

Mayan

Fresco Mural (detail) Mayan

Fresco Mural (detail)

By far the most famous however, are the paintings of Bonampak (Mayan for

'painted walls') a Mayan city state which flourishes in the 9th century.

Discovered in the forests of present day Chiapas in 1946, a series of murals

unfold on the walls and vaulted ceilings of the long stone building that was

once a temple.

Here, in three separate chambers, the strong vibrant colours of New World

frescos are still undimmed by a thousand years of neglect, the inhabitants love

of beads, ornaments, jewelry, and bright clothing, all documented. Along with

Mayan palace life and the upper ruling class. And a desperate hand-to-hand

battle with an invading tribe, dated by the Mayan calendar to the precise date

of August 2nd, 792.

Remarkably preserved for 11OO years despite Mexican humidity, these frescos are

quite unlike ones painted in drier climes. In the inherently humid climate of

Bonampak, local artists, unlike those in desiccated Egypt, enjoyed ample time to

complete their works, with as long as several days of creativity available

before the plaster dried.

ILLUMINATING THE DARKNESS

From the 10th century onwards, manuscript illumination becomes the primary tool

of human expression as the earliest forms of illustrated books begin their

appearance, worldwide. Beginning first in the far east, and surfacing in Europe

in AD 950 as the Dark Ages end, the manuscripts are hand written on vellum,

parchment and early forms of paper and flourishes into the 14th century.

In China and Japan silk or paper scroll paintings are being produced - often

animated and satirical in nature - to accompany written text, with 12th century

The Tales of Gengi by Murasaki Shikibu perhaps the most famous of all.

In Mexico, the Maya are illustrating their books, known as codices, on bark

paper or deerskin.

THE RENAISSANCE: FRESCO REBORN

The fresco is reaffirmed as the number one artistic medium in Renaissance

Europe. Unopposed as yet by oil painting, it becomes a favorite for some of the

world's greatest masters, who produce prodigious numbers of frescoes, most of

which still survive magnificently today, 600 years later. Various forms of

Tempera painting are introduced.

EXPERIMENTS ON PAPER: EUROPEAN BEGINNINGS

Watercolor makes its successful transition to paper in 15th century Europe, with

the early applications used by Albrecht Durer in Germany. He shows how detailed

watercolor sketches and even landscapes can stand on their own, apart from oils.

Later, in 18th century England, Richard Wilson pioneers the use of the medium in

the English Landscape.

THE GREAT AGE OF WATERCOLOUR

The word WATERCOLOR, in use for thousands of years, has managed to become

synonymous with one particular era, one particular place in time: the heroic

landscapes and sweeping pastoral scenes of 18th and 19th century England.

Artists the like of John Sell Cotman, Thomas and Paul Sandby, and JMW Turner -

and many of their contemporaries - were now able to employ the singing tones of

watercolor in capturing atmospheric light and vibrancy, the very essence of

English landscapes. An accomplishment which turned quite ordinary panoramas into

romantic, almost magical visions.

Charles

Burchfield (1893-1967)

Charles Burchfield (1893-1967) is an American original, a maverick

wallpaper designer who stood apart from the artistic currents of his time, and

through perseverance and integrity of vision became one of the most remarkable

painters of the 20th century. Born in Ashtabula Harbor, Ohio, at age five he

moved with his widowed mother to Salem, Ohio. He studied at the Cleveland

Institute of Art from 1912 to 1916 under Henry Keller. He received a scholarship

to study at the National Academy of Design in New York, but quit in

embarrassment after his first day of drawing from a nude model. He returned to

Cleveland to take up work as a wallpaper designer, painting during lunch breaks

and on weekends. He moved to Buffalo in 1921 to work as a wallpaper designer for

N.H. Birge & Sons, then in 1925 to the Buffalo suburb of Gardenville where

he lived the rest of his life. He married in 1922 and eventually raised five

children, but quit his job in 1929 to work on painting full time. His work

became widely known and fairly popular during the "regionalist"

movement of the 1930's, and was handled by the Frank K.H. Rehn Galleries. In

1943 he was elected a member of the National Institute of Arts and Letters, and

after 1949 taught mostly summer art courses at schools in Buffalo, Cleveland and

Minnesota.

Burchfield's earliest paintings, many of them painted during his lunch breaks

from the wallpaper factory and on weekends, are technically unsteady but often

show an extraordinary visual imagination.

Decorative Landscape, Shadow (Willows on Vine Street) (1916, 50x35cm) is a

perceptual puzzle and a poem of transfiguration. From the horizon downward the

painting is simply two trees along a rural street beside a rural house; color

notes are written within the heavily drawn pencil outline. Cover the top of the

picture with a sheet of paper, and there is nothing that any beginning painter

might not have done. But as the trees reach the sky the visual symbols change to

black and white patterns, the branches thinned as if strongly backlit, or

etherealized, and the crown of leaves indicated by strange semaphors and fractal

edges. Is it daylight, or dark? The black form at the upper right could be the

crown of a dark tree, or a sky spangled with stars -- there is no blue in the

sky to tip our impression toward day, but night seems inconsistent with the

colors of the buildings and lawn. The cluster of black dots at the upper right

and the chevrons of small strokes that indicate leaves are painted like the

symbols of a topographical map, or notations of force or movement rather than

form. The picture presents the kind of impossible actuality that is more

familiar in the works of J.C. Escher, but Burchfield pulls it off without any

geometrical distortions, but through his idiosyncratic and uninterpretable

rendering of perfectly familiar objects, and a stylized transfiguration that

hints at spiritual energies, or ominous subconscious urges, or a mind that can

grasp a transcendent dimension within the everyday world without making one seem

more real than the other.

Decorative Landscape, Shadow (Willows on Vine Street) (1916, 50x35cm) is a

perceptual puzzle and a poem of transfiguration. From the horizon downward the

painting is simply two trees along a rural street beside a rural house; color

notes are written within the heavily drawn pencil outline. Cover the top of the

picture with a sheet of paper, and there is nothing that any beginning painter

might not have done. But as the trees reach the sky the visual symbols change to

black and white patterns, the branches thinned as if strongly backlit, or

etherealized, and the crown of leaves indicated by strange semaphors and fractal

edges. Is it daylight, or dark? The black form at the upper right could be the

crown of a dark tree, or a sky spangled with stars -- there is no blue in the

sky to tip our impression toward day, but night seems inconsistent with the

colors of the buildings and lawn. The cluster of black dots at the upper right

and the chevrons of small strokes that indicate leaves are painted like the

symbols of a topographical map, or notations of force or movement rather than

form. The picture presents the kind of impossible actuality that is more

familiar in the works of J.C. Escher, but Burchfield pulls it off without any

geometrical distortions, but through his idiosyncratic and uninterpretable

rendering of perfectly familiar objects, and a stylized transfiguration that

hints at spiritual energies, or ominous subconscious urges, or a mind that can

grasp a transcendent dimension within the everyday world without making one seem

more real than the other.

In 1917 Burchfield experienced some kind of mental crisis or spiritual event

that entirely transformed his painting style. He developed a detailed system of

personal signs, linear forms rather like letters or alchemical signs, that

denoted basic emotions such as fear or despair and that could be woven into his

pictures as decorative patterns or the outlines of everyday objects. He also

settled on a variety of everyday symbols -- birds, stars, sunlight, moonlight,

trees, flowers, dark pools of water -- to represent aspects of himself, his

body, his spiritual yearnings and emotional states. In this early mature style,

natural forms are rendered with abstract, nervous outlines more suitable to a

wood block print or an ikat rug from Tashkent; the colors are flat, without

nuanced washes or diffuse shadows. Some paintings even record the tapping of

woodpeckers or the chirping of crickets as synesthesic vibrating lines and

auras.

Starlit Woods (1917, 85x57cm) shows how Burchfield wove his signs and

symbols into stylized but representational images of astonishing poetry. The

soaring straight tree might represent Burchfield's life, strong but also shorn

of branches and undercut by a gaping dark hole. The profile of this hole has the

"M" shape (repeated in the branch fragments at the top of the picture)

that was Burchfield's sign for fear or anxiety. Beyond the tree a brilliant star

and the brightening horizon stand as natural symbols of hope and renewal,

brought home by the inverted "V" shape of two trees leaning together

in a kind of gothic arch, Burchfield's sign for hope and redemption. But this

simplistic allegory is enriched by the beautiful night scene itself, the

transition of color from the cool sky to the warm grays of the ground, the

fireflies that repeat the swarm of stars. Burchfield is still trying to present

two realities at the same time, but more emphatically and legibly, through the

use of signs and symbols on the one hand and a more thoroughly detailed realism

on the other, both fused in images of natural animism. Quite often Burchfield's

watercolors have an obsessively brushed or muddy appearance, as if amateurishly

worked too long, but he gets exactly the same appearance in his oil paintings as

well, so the effect is intended. This peculiar and unmistakable Burchfield

preference for velvety or leathery brushed textures reappears on a larger scale

in the patterned rendering of the knobby grasses and thatchy branches.

Starlit Woods (1917, 85x57cm) shows how Burchfield wove his signs and

symbols into stylized but representational images of astonishing poetry. The

soaring straight tree might represent Burchfield's life, strong but also shorn

of branches and undercut by a gaping dark hole. The profile of this hole has the

"M" shape (repeated in the branch fragments at the top of the picture)

that was Burchfield's sign for fear or anxiety. Beyond the tree a brilliant star

and the brightening horizon stand as natural symbols of hope and renewal,

brought home by the inverted "V" shape of two trees leaning together

in a kind of gothic arch, Burchfield's sign for hope and redemption. But this

simplistic allegory is enriched by the beautiful night scene itself, the

transition of color from the cool sky to the warm grays of the ground, the

fireflies that repeat the swarm of stars. Burchfield is still trying to present

two realities at the same time, but more emphatically and legibly, through the

use of signs and symbols on the one hand and a more thoroughly detailed realism

on the other, both fused in images of natural animism. Quite often Burchfield's

watercolors have an obsessively brushed or muddy appearance, as if amateurishly

worked too long, but he gets exactly the same appearance in his oil paintings as

well, so the effect is intended. This peculiar and unmistakable Burchfield

preference for velvety or leathery brushed textures reappears on a larger scale

in the patterned rendering of the knobby grasses and thatchy branches.

After a decade of painting in this vatic style (as well as in a lyrical realism

of small town buildings and country nature views), in the late 1920's Burchfield

changed again into a kind of "American Scene" realism that I find

dreary and dispiriting. It seems Burchfield was intentionally capitalizing on

the fashion in "regionalist" painters in the late 1920's and 1930's,

bringing his style toward something more comprehensible and appealing to art

critics and collectors: he had a family to support and was determined to make a

decent living with his art. It worked perhaps too well. He achieved wide notice

as the "Sinclair Lewis of the paintbrush," and was lauded as an

exponent of a uniquely American art, and to my eye never painted anything that

showed a glimmer of joy or humor. But in 1943 -- with his family raised, his

success assured, newly elected to the National Academy and feeling the willful

liberty of late middle age -- Burchfield had another revelatory episode that

turned him back to his youthful style, his old symbols and signs, and his nature

animism. In this last phase he often took up his youthful paintings and reworked

or completely repainted them, sometimes adding paper around the edges to

substantially enlarge the sheet.

Hot September Wind (1953, 99x74cm) is a lovely work from these late years.

The yellow patterns over the gray sky symbolize both the heat of the late day

sun and the oncoming blast of hot wind. The downward twist of the flowers along

the bottom of the picture shows that the wind is striking us in the face,

bringing with it all the dry smells of late summer; the flowers' curving backs

suggest a visual pattern that is repeated in beautifully varied earth tones into

the dry grasses and the distant hump of trees. And centered in the picture,

hovering like the dry sound of swishing grass stalks, ragged like the ripples of

gusts in the wheat or the pressure of wind against the eyes, is the old

"M" symbol of fear, the winnowing fear of life about to enter its

inevitable decline. But the fear is tempered by the warmth and richness of the

natural world, the cycle of seasons, and the harvest of a lifetime spent in art.

Hot September Wind (1953, 99x74cm) is a lovely work from these late years.

The yellow patterns over the gray sky symbolize both the heat of the late day

sun and the oncoming blast of hot wind. The downward twist of the flowers along

the bottom of the picture shows that the wind is striking us in the face,

bringing with it all the dry smells of late summer; the flowers' curving backs

suggest a visual pattern that is repeated in beautifully varied earth tones into

the dry grasses and the distant hump of trees. And centered in the picture,

hovering like the dry sound of swishing grass stalks, ragged like the ripples of

gusts in the wheat or the pressure of wind against the eyes, is the old

"M" symbol of fear, the winnowing fear of life about to enter its

inevitable decline. But the fear is tempered by the warmth and richness of the

natural world, the cycle of seasons, and the harvest of a lifetime spent in art.

Burchfield is among the most difficult 20th century American painters to

approach intimately. It is tempting to cast his paintings as the work of a

provincial, quirky and sometimes mentally disturbed talent following its own

inclinations. But this ignores Burchfield's attentive response to contemporary

art trends, his rewriting and manipulated release of his diaries to fabricate a

public artistic persona, and his obvious ambition and hard work. Burchfield may

have capitulated to art trends in his "regionalist" paintings, but his

early and late works show a brilliant visual imagination restlessly seeking the

artistic equivalents for a transcendental and highly individual vision of the

natural world.

There is no comprehensive reference to Burchfield's work, which is scattered

across many collections and has not yet been definitively catalogued. The

Paintings of Charles Burchfield: North by Midwest by Nannette Maciejunes &

Michael Hall (Harry Abrams, 1997) contains a large selection of paintings and 9

essays by art scholars, and is probably the best single introduction to his

range. Charles Burchfield by Matthew Baigell (Watson-Guptill, 1976), now out of

print, is an interesting survey and appreciation of Burchfield's work, marred by

the large number of black-and-white reproductions and a superficial grasp of the

paintings. The Whitney Museum's Charles Burchfield, the catalog to its 1956

retrospective exhibit, is a brief overview and appreciation of his work while he

was still alive -- again with too many black-and-white reproductions.

|

| Features On Site |

About Photography

About Pottery

About Sculpting

About Acrylic Painting

About Wood Working

|

|

| Art Museums |

McMichael Art Collection

Mercer Union Gallery

Art Gallery of Ontario

National Gallery

Art Gallery of Hamilton

Beaverbrook NB

|

|

| Featured Artist |

Northern Territory Australia

Aboriginal Rock Painting |

|

| Featured Artist |

Brazil

Oldest Rock Art in New World |

|

| Featured Artist |

Prehistoric Bison

Altamira Cave |

|

| Featured Artist |

Prehistoric Bull

Lascaux Cave |

|

| Featured Artist |

Egyptian Banquet

Tomb of Nakht (detail) |

|

| Featured Artist |

Egypt, Hunting and Fishing Scene

Tomb of Horemheb, Thebes (detail) Archeological Museum, Heraclion, Crete |

|

| Featured Artist |

Minaon Beauty

Knonssos |

|

| Featured Artist |

Tomb of Etruscan Nobleman

(detail) Tomb of the Augurs |

|

| Featured Artist |

Attorney Terentius Neo and His Wife

From Pompeii. Museo Nazionale, Naples |

|

| Featured Artist |

Chinese

Deer in Autumn Forest (detail) |

|

| Featured Artist |

Chinese, Huang Chutsai

Partridge and Sparrow (detail) |

|

| Featured Artist |

Sutra Painting

c. 750 AD

Atami Museum, Kanagawa Prefecture. |

|

| Featured Artist |

Night-Shining White, Tang dynasty (618–907), 8th century

Attributed to Han Gan (Chinese, act. 742-756)

China. Handscroll; ink on paper; 12 1/8 x 13 3/8 in. (30.8 x 34 cm)

Metropolitan Museum of Modern Art.

Han Gan, a leading horse painter of the Tang dynasty (618-907), was known for portraying not only the physical likeness of a horse but also its spirit. This painting, the most famous work attributed to the artist, is a portrait of Night-Shining White, a favorite charger of the emperor Xuanzong (712-756). The fiery-tempered steed, with its burning eye, flaring nostrils, and dancing hooves, epitomizes Chinese myths about imported "celestial steeds" that "sweat blood" and were really dragons in disguise. This sensitive, precise drawing, reinforced by delicate ink shading, is an example of "baihua" (white painting) a term used in Tang texts on painting to describe monochrome painting with ink shading, as opposed to full color painting. The later term "baimiao" (white drawing) denotes line drawing without shading, as seen in the paintings of Li Gonglin (ca. 1041-1106). The numerous seals and inscriptions added to the painting and its borders by later owners and experts are a distinctive feature of Chinese collecting and connoisseurship. While collectors are sometimes overzealous in showing their appreciation in this manner, the addition of seals and comments by later viewers served to record a work's transmission and offer vivid testimony of an artwork's continuing impact on later generations. |

|

| Featured Artist |

Betty Carr

"Garden Reflections"

Watercolor 23" x 30" (Detail). |

|

| Featured Artist |

Sally Cataldo

"Still Life After Edward Hopper". |

|

| Featured Artist |

John Marin,

Lower Manhattan, 1920.

Watercolor and charcoal on paper, 55.4 x 68 cm. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, The Philip L. Goodwin Collection. Photograph © 1998 The Museum of Modern Art, New York |

|

| Featured Artist |

JOHN MARIN

(1870 - 1953 American)

A prominent New York architect who became an artist, John Marin earned a reputation for abstract watercolor paintings influenced by Cubism and Futurism. He was one of the Taos, New Mexico Colony painters in the late 1920s, and his work is credited as an important precedent to Abstract Expressionism.

Marin was born in Rutherford, New Jersey, and grew up in nearby Weehawken. He attended the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, studying with Thomas Anshutz, then studied at the Art Students League in New York, and from 1905 to 1909, studied in Europe. In Paris, he associated with the Fauvist circle.

He had a long association in New York City with Alfred Stieglitz, who exhibited his work, and in the 1930s, he developed interest in the human figure and marine subjects and oil painting.

In Taos, he was the guest of Mabel Dodge Luhan, and was unique because he was using a dry brush watercolor technique and vividly demonstrated how watercolor could capture the New Mexico landscape. Because he was so respected nationally, his use of watercolor in New Mexico set a precedent for others painting there. |

|

| Featured Artist |

John Marin (1870-1953)

Top of Radio City, 1937

Watercolor, graphite & charcoal on paper; 20 3/4 x 24 3/4 inches. Signed lower right. |

|

| Featured Artist |

John Marin

(1870-1953)

Herring Weirs, Deer Isle, Maine 1928

Watercolor on paper

15 1/2 x 20 1/4 inches

Signed and dated lower right: "Marin 28" |

|

| Featured Artist |

Edward Hopper, American, born 1882

Born in 1882 in Nyack, N.Y., Hopper first became known for his etchings. He had painted since his student days at the Chase School, where he was a classmate of George Bellows, Guy Penn du Bois, and Rockwell Kent, but his artwork brought him little attention and for a number of years he made his living as an illustrator, a career he found unsatisfying and frustrating.

While vacationing in Gloucester, Mass., during the summer of 1923 he began working in watercolors at the suggestion of Jo Nivison, an artist who became his wife the following year. Away from New York and working outdoors in a medium that demanded quick choices, Hopper was at his freest. He drew from visually complicated subjects -- lighthouses along the shore, gabled and dormered Victorian houses -- to create images specific to real locations, a direct contrast to the invented settings of the etchings and paintings of his urban artworks.

The watercolors, composed only by Hopper's choice of vantage point, capture subtle and ephemeral shifts in the light and air of a particular moment and place. In them he examines crisp New England landscapes, the dramatic perspectives and intense sunlight of Mexico, and haunting vestiges of the Civil War in Charleston. Hopper repeatedly turned to lighthouses and Victorian architecture as symbols of the past. By setting these subjects adjacent to utility poles, railroad tracks, or other references to progress, he elicited a dialogue between past and present and alluded to change as a fundamental characteristic of American life.

The watercolors from the summers of 1923 and 1924 catapulted Hopper to fame. The Brooklyn Museum purchased The Mansard Roof after including it in their 1923 watercolor show, and all sixteen paintings in a 1924 exhibition at Frank K. M. Rehn's New York gallery sold. In The Mansard Roof (1923), a sun-washed pile of a house, fluid forms of foliage and shadows dance to the same breeze that billows the yellow awnings. "He captured the temperature of the air, a breath of wind, the rustling of dry grasses-an aura of timelessness very different from the psychic urgency so often found in his urban scenes," said curator Mecklenburg. In Funnel of Trawler (1924) the interplay of light and shadow combines with unusual cropping to create a sense of immediacy.

Hopper visited Cape Cod for the first time in 1930 and he and Jo returned each summer to paint, building a modest house there in 1934. While the watercolors produced during the 1930s are less spontaneous, they exhibit a greater sense of compositional finesse and take on a more modernist edge. Roofs of the Cobb Barn (1931) emphasizes the clean geometric forms and white planes of the barn roof.

In his later watercolors Hopper engaged the textured surface of the paper through drybrushing and relied less on washes. Cottages at North Truro (1938) illustrates this "toothier" approach. It also unites two important Hopper themes, vernacular architecture and railroad references, in a complex and dramatic landscape.

By the late 1930s his work was becoming more restrained in both style and method. Hopper had exhausted the Cape Cod area for imagery, and he and Jo began traveling elsewhere for subject matter. Several of the late watercolors were painted in Mexico; Monterrey and the Spanish colonial town of Saltillo provided inspiration for Monterrey Cathedral, Saltillo Mansion, and Saltillo Rooftops, works from the summer of 1943.

Edward Hopper's regular forays in watercolor ended with a trip West and into Mexico in 1946. Asked in 1960 if he gave up watercolor out of a preference for working slowly, he replied, "I don't think that's the reason I do fewer watercolors. I think it's because the watercolors are done from nature and I don't work from nature anymore." |

|

| Featured Artist |

Charles Burchfield

(American 1893-1967)

Detail from The Open Road, 1931, Watercolor and gouache on paper. Montgomery Museum of Fine Arts Association Purchase. |

|

| Featured Artist |

Charles E. Burchfield

The Golden Glow of Summer, 1964,

Watercolor; 40 x 29 inches |

|

| Featured Artist |

Charles Burchfield

November Sun Emerges |

|

| Featured Artist |

Charles Burchfield

(1893-1967) |

|

|

Artist Number 1

Artist Number 1

Artist Number 2

Artist Number 2

Artist Number 3

Artist Number 3

Artist Number 4

Artist Number 4

Artist Number 5

Artist Number 5

Artist Number 6

Artist Number 6

Artist Number 7

Artist Number 7

Artist Number 8

Artist Number 8

Artist Number 9

Artist Number 9

Artist Number10

Artist Number10

Decorative Landscape, Shadow

Decorative Landscape, Shadow  Starlit Woods (1917, 85x57cm) shows how Burchfield wove his signs and

symbols into stylized but representational images of astonishing poetry. The

soaring straight tree might represent Burchfield's life, strong but also shorn

of branches and undercut by a gaping dark hole. The profile of this hole has the

"M" shape (repeated in the branch fragments at the top of the picture)

that was Burchfield's sign for fear or anxiety. Beyond the tree a brilliant star

and the brightening horizon stand as natural symbols of hope and renewal,

brought home by the inverted "V" shape of two trees leaning together

in a kind of gothic arch, Burchfield's sign for hope and redemption. But this

simplistic allegory is enriched by the beautiful night scene itself, the

transition of color from the cool sky to the warm grays of the ground, the

fireflies that repeat the swarm of stars. Burchfield is still trying to present

two realities at the same time, but more emphatically and legibly, through the

use of signs and symbols on the one hand and a more thoroughly detailed realism

on the other, both fused in images of natural animism. Quite often Burchfield's

watercolors have an obsessively brushed or muddy appearance, as if amateurishly

worked too long, but he gets exactly the same appearance in his oil paintings as

well, so the effect is intended. This peculiar and unmistakable Burchfield

preference for velvety or leathery brushed textures reappears on a larger scale

in the patterned rendering of the knobby grasses and thatchy branches.

Starlit Woods (1917, 85x57cm) shows how Burchfield wove his signs and

symbols into stylized but representational images of astonishing poetry. The

soaring straight tree might represent Burchfield's life, strong but also shorn

of branches and undercut by a gaping dark hole. The profile of this hole has the

"M" shape (repeated in the branch fragments at the top of the picture)

that was Burchfield's sign for fear or anxiety. Beyond the tree a brilliant star

and the brightening horizon stand as natural symbols of hope and renewal,

brought home by the inverted "V" shape of two trees leaning together

in a kind of gothic arch, Burchfield's sign for hope and redemption. But this

simplistic allegory is enriched by the beautiful night scene itself, the

transition of color from the cool sky to the warm grays of the ground, the

fireflies that repeat the swarm of stars. Burchfield is still trying to present

two realities at the same time, but more emphatically and legibly, through the

use of signs and symbols on the one hand and a more thoroughly detailed realism

on the other, both fused in images of natural animism. Quite often Burchfield's

watercolors have an obsessively brushed or muddy appearance, as if amateurishly

worked too long, but he gets exactly the same appearance in his oil paintings as

well, so the effect is intended. This peculiar and unmistakable Burchfield

preference for velvety or leathery brushed textures reappears on a larger scale

in the patterned rendering of the knobby grasses and thatchy branches. Hot September Wind (1953, 99x74cm) is a lovely work from these late years.

The yellow patterns over the gray sky symbolize both the heat of the late day

sun and the oncoming blast of hot wind. The downward twist of the flowers along

the bottom of the picture shows that the wind is striking us in the face,

bringing with it all the dry smells of late summer; the flowers' curving backs

suggest a visual pattern that is repeated in beautifully varied earth tones into

the dry grasses and the distant hump of trees. And centered in the picture,

hovering like the dry sound of swishing grass stalks, ragged like the ripples of

gusts in the wheat or the pressure of wind against the eyes, is the old

"M" symbol of fear, the winnowing fear of life about to enter its

inevitable decline. But the fear is tempered by the warmth and richness of the

natural world, the cycle of seasons, and the harvest of a lifetime spent in art.

Hot September Wind (1953, 99x74cm) is a lovely work from these late years.

The yellow patterns over the gray sky symbolize both the heat of the late day

sun and the oncoming blast of hot wind. The downward twist of the flowers along

the bottom of the picture shows that the wind is striking us in the face,

bringing with it all the dry smells of late summer; the flowers' curving backs

suggest a visual pattern that is repeated in beautifully varied earth tones into

the dry grasses and the distant hump of trees. And centered in the picture,

hovering like the dry sound of swishing grass stalks, ragged like the ripples of

gusts in the wheat or the pressure of wind against the eyes, is the old

"M" symbol of fear, the winnowing fear of life about to enter its

inevitable decline. But the fear is tempered by the warmth and richness of the

natural world, the cycle of seasons, and the harvest of a lifetime spent in art.